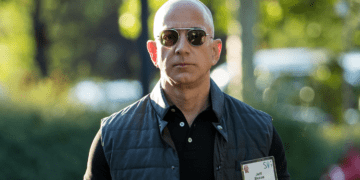

According to an early forensic report, Jeff Bezos’ phone was violated by Saudi officials, with the attack appearing to have come directly from Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s phone number

The United Nations wants to launch an investigation after a first forensic report that Jeff Bezos’ phone was hacked “most likely” by Saudi state officials. How? Apparently, they used a mobile hack, perhaps the one created by the NSO group, Pegasus, to penetrate the security of the smartphone of Amazon founder and owner of the Washington Post.

According to the observations made by the experts cited by the United Nations last Wednesday, it seems that mobile spyware was exploited to exfiltrate gigabytes of data from the Bezos phone last May, after about six months that the Saudi government had managed to get the software. The forensic report comes about a day after the news of the hacking of Bezos’ smartphone was released, and inside it, there is sometimes astonishing information.

Bezos’ smartphone hacked, how it happened

One of them is the fact that the malware was delivered to the Amazon founder’s device by a number belonging to Mohammad bin Salman, Crown Prince, Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister of Saudi Arabia. The report, signed by FTI Consulting, indicates as “highly likely” that Bezos’ smartphone was tampered with using a malicious video sent via WhatsApp. In just a few hours, the malware managed to transfer a large amount of data from the smartphone.

According to UN officials who had access to the forensic report, the violation of Bezos’ phone was part of a “targeted surveillance system aimed at alleged opponents and exponents of broad strategic importance to the Saudi authorities”. The report does not exclude that the attacker used technologies, not from NSO, but developed by another mobile malware manufacturer. The Saudi government has already rejected all the statements in the report, calling them “absurd”.

The NSO Group, responsible for malware used by several governments around the world, has also responded, claiming that its software “was not used in this case”, stating that its technology does not work on American numbers. Any reference to the group in the case of Bezos could be called; he said, “defamatory”.

According to what is known today, forensic experts began observing Bezos’ smartphone after the latter had accused the National Enquirer of blackmail last year. In a post written on Medium Bezos claimed that he had been targeted by the tabloid, which had gotten its hands on private text messages and photos obtained from his device and published them. The founder of Amazon had written that he would soon start an investigation into the incident.

The first report of the investigation indicates that the first violation occurred after Bezos and Mohammad bin Salman exchanged phone numbers in April 2018, a month before the hack. The same malware used in the Bezos phone hack was also used on the devices of other Saudi opponents and political activists during the same period, including those of members close to Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist who had repeatedly exposed himself against the Saudi government and was assassinated in October 2018. In that case, American intelligence had concluded that Bin Salman had commissioned the murder.

According to the experts cited by the United Nations, there could also be an involvement of the Crown Prince in the surveillance of Bezos, to influence, if not even prevent, the Washington Post’s reporting on what is happening in Saudi Arabia. The Saudi government would then purchase the Pegasus malware from the NSO Group and use it – via WhatsApp – to install the malware on Bezos’ device.

WhatsApp has already taken the NSO Group to court for creating and using Pegasus in the messaging platform and proposing it to third-party agencies. Once applied on the smartphone, malware can, in some cases intervene in a completely transparent way allowing operators to retrieve data from the device. The United Nations said it would continue its investigation to find out as much detail as possible about the “growing role of the surveillance industry” used to target journalists, human rights advocates and publishers.